“What is man?” is an age-old question. Another question we should also ask is, What’s wrong with man? Because we are fraught with trouble that we cannot easily grasp. Things are not right with human nature, but how to make sense of our psychological ills – that is the question.

Blaise Pascal had an astute understanding of this human dilemma; indeed, few had the penetrating insights that he expressed with such incisive prose: “Man is neither angel nor beast, and it is unfortunately the case that anyone trying to act the angel acts the beast” (§678/358).

Speaking of the unity in man of mind and matter, Pascal writes: “This is the thing we understand least; man is to himself the greatest prodigy in nature, for he cannot conceive what body is, and still less what mind is, and least of all how a body can be joined to a mind. This is his supreme difficulty, and yet it is his very being. The way in which minds are attached to bodies is beyond man’s understanding, and yet this is what man is” (§199/92).

But there is another duality in our nature that Pascal points up: some, he says, are “exalted at… the sense of their greatness” while others are “dejected at the sight of their present weakness… If they realised man’s excellence [but] they did not know [man’s] corruption… the result [is] … pride, and if they recognised the infirmity of nature, [without knowing] its dignity… the result [is] that they… fall headlong into despair.” So he sums up: “We feel within ourselves the indelible marks of excellence, and is it not equally true that we constantly experience the effects of our deplorable condition?” (§208/435).

“Who cannot see that unless we realise the duality of human nature we remain invincibly ignorant of the truth about ourselves?” (§131/434).

So, is man good and glorious? Or is he weak and wicked?

“What shall become of man? Will he be the equal of God or the beasts? What a terrifying distance! What then shall he be? Who cannot see from all this that man is lost, that he has fallen from his place, that he anxiously seeks it, and cannot find it again? And who then is to direct him there? The greatest men have failed” (§430/431).

“You are a paradox to yourself” says Pascal – echoed by Professor of Psychology Jordan Peterson, “You are too complex to understand yourself”. We need help!

“Men, it is in vain that you seek within yourselves the cure for your miseries. All your intelligence can only bring you to realise that it is not within yourselves that you will find either truth or good” (§149/430).

“Know then, proud man, what a paradox you are to yourself. Be humble, impotent reason! Be silent, feeble nature! Learn that man infinitely transcends man, hear from your master your true condition, which is unknown to you. Listen to God.” (§131/434).

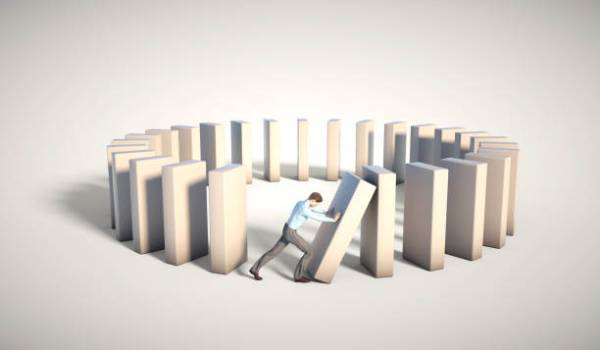

When we are seriously ill without realising it, a doctor’s diagnosis is hard to take. So also it is humbling to face up to our existential pain, when our pride is the main problem, and our pride is hurt.

On the other hand, a doctor’s mistaken diagnosis can be very harmful for a patient, because the remedy proposed may actually be detrimental to the patient’s health. So it is with our human predicament: many a wrong diagnosis of our ills has only led people into further distress. So, what is wrong with us? Where is the doctor who can bring the right diagnosis?

“Listen to God”. Only our Maker can mend us.

Clive Every-Clayton