Some parts of the modern-day church are called “Reformed.” One may wonder why. Should the church need reforming? May she have gone off course? Is she infallibly held in the truth or may she become corrupted? If so, what authority is competent to reform her? Is it even thinkable that anyone may be able to reform the church? The church is a global phenomenon of believers in Jesus, divided into innumerable groups, some large, some small. It is so huge that no-one can grasp the whole with a view to reforming it, not even the Pope.

So while some want a progressive or reforming Pope and others insist on a traditional Pope, there are already two dividing tendencies within the Roman Church, quite apart from the many other kinds of churches. And if one wants to “reform” the church, by what criteria might it be reformed?

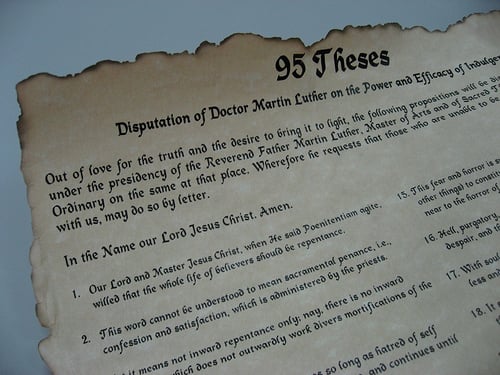

The 16th century saw what came to be called “the Reformation”. The moral quality of the church and its leadership had suffered a sad decline over the previous century. Even Roman Catholic historians admit the immoral behaviour of some Popes left a lot to be desired. Their conduct was unworthy of the Lord Jesus Christ whom they professed to serve.

Apart from that moral decline, the reformers discerned theological errors that had been adopted in the church’s teaching and practice. How did they know there were errors? By a return to studying the Bible.

Martin Luther was a monk whose task was to teach theology. He therefore studied the Scriptures that he had to teach. As he did so, he struggled to understand some key concepts that were fundamental to the Gospel message, notably those of righteousness and justification. He had his own personal struggle to become righteous, being very conscious of his inner faults, spending a lot of time in confession. He was at the same time puzzling over St Paul’s teaching on the theme of justification, notably in the epistle to the Romans chapters 1-5.

After a lot of soul-searching and Bible study, he finally found the key that he had never grasped before: how God “justified” (i.e. declared legally just and acceptable in the judgment) those who believe in Jesus, the Saviour who died and rose again for their salvation. None of his confessors or colleagues at university had been able to share this good news with him, for they neither taught it nor understood it themselves. But there it was in the New Testament!

It was this rediscovery of the Bible’s message of “justification by faith in Christ” that led to the reformation and birthed the “reformed church”. While official church leaders condemned Luther, many were glad to receive the message of salvation by faith in Christ. They studied the Bible to find the truth of God, and by that truth they sought to reform the church’s moral laxity and its inadequate teaching on justification.

When challenged as to why they held their doctrines, their answer was simply, “Because the Bible says so.” The Bible was henceforth to be the sole authority to which Christians should absolutely adhere. In any dispute, the way to resolve it was always by a return to studying what the Bible actually says. This remains the principle of the reformed church.

Unfortunately, the temptation to allow passing philosophical trends to influence theologians has led parts of the church to drift from biblical faithfulness. Wisely did the Reformers insist that the church should be “semper reformanda” – continuously reforming itself by Holy Scripture, maintaining the purity of both its holiness and its biblical doctrine.

Clive Every-Clayton